Sunday, June 22nd

North Hollywood, California

Dear all,

I hope everyone had a fine weekend. I think it was for all of you, too, but I don’t really keep up with the news anymore for it doesn’t concern me anymore. I could pull up my Iranian heritage from my Ancestry DNA test and write a whole political speech, but that would bore all of you (myself included) and I won’t bother.

I used to care a lot about world events, but lately? I’m not sure the world has ever cared so much about me. (And they should.)

What matters most to me right now is my prescription nose job, which has just been rescheduled… pushed two weeks out because my surgeon had a “family emergency.”

Naturally, I’m devastated.

I’ve always thought that nose job bandages were a bold fashion statement, kind of like having a boyfriend, only quieter and far more reliable. They’re loud without saying anything at all. There’s something beautifully punk about walking around with your face in recovery, while you yourself are too, like showing up to your detox center in LA half-baked straight out of a jeep from Las Vegas with your lips augmented, waiting for the swelling to go down, waiting for the self-destructive urges to go down, too.

The nose job says: I’ve transcended the flesh. I’ve handed my bones over for public examination and came back changed.

I’ve been fantasizing about sitting in my AA meetings (which I’ve recently become addicted to), saying nothing at all, just letting the bandages speak for me. Maybe it’s a female urge, but I rather like the idea of being outwardly wounded, even if it is only temporarily. It sends a message.

I’ve been dreaming of this moment since I was fifteen. And now it’s finally happening. (In July…)

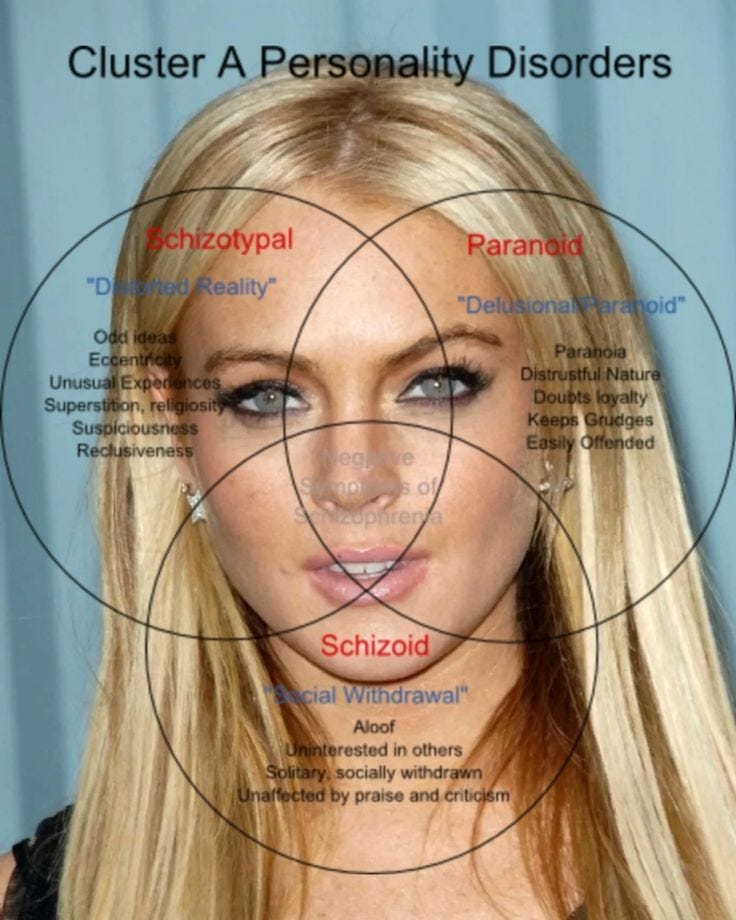

Aside from that personal tragedy, I’d say that my weekend was actually pretty okay. On Friday night, my housemate and I watched The Crush. It’s one of those very campy, very pinterest-worthy movies you can watch over and over again to delude yourself in a carefully curated, yet beautifully written self-induced psychosis, in the same vein of movies centered around the complexities of female delusion such as Black Swan, Buffalo ‘66, and The Virgin Suicides.

We got the idea on the drive home from karaoke, (where I bodied, of course) when I realized us two live dangerously close to a sacred cinematic landmark: the spot where Cher got robbed in Clueless.

Alicia Silverstone was also a patient at this one acupuncture clinic that he worked at, but you didn’t hear it from me…

We both like boys, so I figured a movie about a young Cary Elwes (plenty of male actors, like James Franco, age like fine wine. Not him, sadly…) being sexually harassed by a fourteen year old girl would be a perfect fit for the evening while we both are recovering from severe mental illness at the sober living home.

The premise of The Crush follows a twenty eight year old journalist named Nick, moving to Seattle for a better life, into a dreamy guesthouse in the suburbs on a sprawling estate, ready to start fresh.

What he doesn’t plan on is Adrian, his landlord’s daughter, watching him like a cat watches something soft and trembling. At just fourteen, she disturbingly self-assured, like a girl who grew up with everything she wanted but nothing of what she needed.

I couldn’t help but think: Adrian is a Newport Academy girl. She would’ve been my roommate in the co-occurring diagnosis ward, at the gender-separated 120 acre ranch.

Newport Academy is the place where they send girls who get labeled too much… too intense, too sexual, too angry. It’s where the children of parents too lazy, too ashamed, or too terrified to actually parent go to be “straightened out.”

Newport Academy is for the girls who get punished for doing out loud what everyone else only dares to fantasize about in silence. (Paris Hilton went to a program similar, and that’s all you need to know…)

Did Newport Academy fix me? What do you think, dear reader, did it?

At first, it made me rebel harder. I searched for love in the outside world, in places that felt like freedom but were really just different kinds of abandonment.

But now, as an adult, I can admit there was something strange and almost liberating about being in a place like that. (Despite my violent resistance at the time, I kind of miss Newport Academy... life was so simple…)

When everyone around you thinks you're so sick beyond repair and you might as well be untouchable, there's a kind of freedom in that. No one expects anything from you. You’re left alone long enough to focus on what actually matters to you… like writing useless, beautiful little thought pieces on Substack for the people you meet on the internet, while pretending your life is under control.

But really, you’re just searching for the self you never got to become… the one you missed out on as a young girl because you were too busy surviving. (And now we are here. I’m hoping to grow up soon, but I know these things take time, like a plant who needs room to grow but whose roots have constantly been displaced.)

Which brings me back to the Crush. This movie isn’t just a story of a teenage girl gone wild. It’s a story about denied desire, blurred power, and the quiet thrill of danger dressed up as restraint. It is truly a coming-of-age story.

The Crush doesn’t just ask what happens when someone crosses a line… it dares to ask what happens when you secretly wanted them to, and I will try to explain it in the least revealing way possible, so all of you can enjoy the movie organically.

It's one I’ve seen before, tucked among the provocative thrillers of the ’90s, but what I’ve realized is that certain films only fully reveal themselves after time has passed, not just time in history, but time in relation to the self.

Either way, like the Mandela effect, when you revisit a movie, there are elements that just appear, things you didn’t see before. Not just plot points or camera angles, but entire truths, lurking between the lines of sanity and taboo.

Something that strikes me about the pre-9/11 era of film is the sheer lack of filter. There’s a rawness, a fearlessness in those stories. They weren’t afraid to be provocative, to be wrong, to push buttons or cross lines. It was messy. Unapologetic. Alive. And that’s what art should be, an act of freedom. As long as no one is harmed in its creation, art should never be censored. Art is only a reflection of real life.

Mass censorship isn’t moral purity, it’s the first step toward fascism. And I’m one of those ones who would rather be dead than live without the oxygen of freedom. It’s a soul-level truth. That’s how much faith I have about what’s waiting for me on the other side, when every single day feels like going to Vietnam and back.

What happens to those that survive the war? Where do they end up going when everyone around them is gone?

Death, to me, wouldn’t be something sad. It would feel like coming home after a long day out in the cold, to somewhere warm, quiet, and familiar. They say you have to suffer to be alive, but I don’t believe that. This mentality really only benefits the exploitative proletariat.

I think falling in love is just the body’s way of rehearsing death, a gentle microdose of what it might feel like to finally let go, which is why the French refer to orgasms as la petite mort, or “the little death”.

To me, not being free feels unnatural. I’ve always been more spirit than body. Placing my mind in a cage is like being locked out of your house and never getting to go home again, or worse, realizing home was never really yours to begin with, (which is what I learned when I came back from Newport Academy at seventeen years of age).

So, recently, I came to a conjunction in my life. The perfect opportunity to escape like I had always wanted found a clearing for me, and I seized it, thinking, what better way to chase that feeling of freedom than by driving across the United States?

Maybe it is during a war against human consciousness, sure, but it was a dream I used to cling to while staring at my employee badge in the teacher’s lounge at work, fantasizing about palm trees and Hollywood hills instead of cornfields, screaming ungrateful children unworthy of my wisdom, and quiet despair.

And now, I’m here, only because my imagination led the way.

I dared to dream, and now I’m beginning to understand just how much I’ve manifested every part of my life… the beauty, the mess, the miracles and the wreckage.

That’s the power of imagination. Which is exactly why it’s so heavily policed when we’re young. Because to imagine a life beyond survival is a direct threat to the machine. Imagination creates the kind of person who won’t say “yes” to a life of quiet resignation. The kind of person willing to risk death just to feel alive somewhere else.

And this spirit… reckless, radiant, unwilling to settle… is the same one that’s driven immigrants across oceans, generations deep. It is the true, original spirit of America, and it’s not just a biological urge. It’s a soul urge.

Whilst in a world where freedom is so often denied, imagination becomes the last wild place left. It’s where the soul takes its shoes off, where the inner world runs untethered.

Few lucky ones get to project that inner world onto a screen. And if you’re paying close enough attention, you can feel everything they’re feeling… the ache, the danger, the risk. The wanting.

Forget the surface-level thriller. The Crush is a dangerously sexy, twisted tale of a man shackled by his own suppressed lust, and the catastrophic fallout when desire claws its way out in all the wrong ways.

And what struck me this time with a kind of eerie clarity, is that The Crush is far more than a cautionary tale about an obsessive teenage girl. It’s a study in projection. Shame. Desire. Denial. It’s a mirror held up to its writer.

This movie was written and directed by a man, and it shows. The film unfolds entirely through his gaze. We’re not watching Adrian as she sees herself. We’re watching her through Nick’s eyes, and by extension, Shapiro’s. That’s not inherently a flaw, but it’s essential to understand. This isn’t her story… it’s his fantasy.

Nick isn’t just a victim of a teenage girl’s obsession. He’s a man drowning in craving, a craving so taboo it scorches every inch of him. His furtive glances, nervous deflections, half-hearted boundaries, none of it reads innocent. It reads addicted.

Adrian, all youth and danger and magnetic force, becomes the object of his most illicit fantasies… fantasies he desperately tries to choke down beneath the mask of a “journalist minding his own business”. But lust has a way of finding the cracks within an individual and filling them in, at least only temporarily.

Because in The Crush, Adrian becomes the projection of a man's most dangerous desire, one many are unwilling to admit to themselves, (though I’ve encountered this several times) the young, precocious girl who just "goes too far." She’s both temptation and threat, extremely desirable, and punishable for being so.

It’s the classic Madonna/whore switch, just reloaded into a different frame, one of a girl not yet a woman, but learning how to be. And yet, if you look closely, something more bizzare is happening under the surface. Something the movie itself maybe doesn’t seem to be fully aware of.

Nick and Adrian are mirrors of each other. That’s what haunts me most.

He isn’t just the unwilling object of Adrian’s attention. He’s drawn to her. Not overtly, not in a way the script will ever explicitly admit, but it’s there. In the lingering glances. The half-smiles. The doors left cracked open. He plays innocuous, but repression doesn’t make someone clean. It just makes them dishonest. What we’re watching is a man at war with himself, refusing to acknowledge the taboo feelings inside him, and in doing so, projecting all that anxiety and shame onto Adrian.

And Adrian? She responds to that unspoken tension like an emotional tuning fork. She sees what he won’t name. She absorbs it, reflects it, pushes it into the open. Her actions are extreme, yes. Violent. Obsessive. But they’re also the mirror image of Nick’s avoidance.

He is passive-aggressive; she is aggressive-aggressive. He represses desire; she throws it in his face. He retreats; she invades. Together, they form a closed circuit of energy; shame, power, projection, all building towards explosion.

The age gap between them matters, too… not just legally, but symbolically. She, at fourteen, represents youth, chaos, sexual danger. He represents aging control, the pressure to remain morally above the fray. But both of them are playing parts. Adrian is too young to hold all the meaning the story puts on her. Nick is too dishonest with himself to admit he’s tempted.

The tragedy of The Crush is that it pretends to be a one-sided story about a girl who doesn’t know her place, but underneath, it’s a two-way psychological entanglement made toxic by silence and shame.

Every door Nick opens, every moment he entertains her, is a quiet surrender, a breathless dive into the forbidden. His repression doesn’t protect him. It devours him. And by the time he realizes what he's done, it’s already too late. Adrian’s obsession becomes a reflection of his own rot, his cowardice, his denial, his refusal to own the hunger that burns inside him.

The Crush doesn’t moralize. It seduces. It makes you sit with the discomfort of desire, the kind that doesn’t fit inside the lines. It’s a raw, electrifying dance of power, perversion, and ruin, where the lines between victim and perpetrator blur in the smoke and heat. This movie doesn’t play it safe. It opens its mouth and screams: This is what it looks like when you try to bury the parts of yourself you’re too afraid to admit exist.

And what’s most damning? The film itself doesn’t seem to know this. It is only through the careful lens of an outside observer for these things to be noticed.

Because it was written by a man… a man who, consciously or not, can’t step outside of Nick’s point of view. Adrian is never given true interiority. We don’t know why she is the way she is. Her trauma, her inner world, her emotional logic are all secondary to Nick’s inner crisis. And in that sense, The Crush is a document of male anxiety, the fear of being desired by someone you’re not “allowed” to want, and the panic of being caught in the act of wanting them back.

This is why it still matters. Why it still unsettles. The Crush isn’t just about obsession, it’s about the consequences of denial. About what happens when a man refuses to see himself clearly, and instead casts his own shadow onto someone younger and more vulnerable.

It’s not a clean story. It’s a bizarrely raw one, a story about reflection, and what happens when you smash the mirror instead of facing what’s inside it.

So maybe The Crush unsettles us because it doesn’t give us the comfort of resolution. It doesn’t let us draw a clean line between right and wrong, truth and fantasy.

And that’s what makes it art, where the truth, (real truth, not the garbage you see on the news) lives, somewhere in the blurry places. And maybe that’s why I write at all. Not to offer clean answers, but to sit with the contradictions. To take the parts of girlhood I wasn’t allowed to keep and hold them up to the light, even if they’re cracked, even if they make people uncomfortable.

Because the point was never to be palatable. The point was to be free.

And freedom, as I’m learning, doesn’t always look like driving west whilst blasting Megan Thee Stallion going one hundred miles per hour on Historic Route 66 over sacred Native American territory.

Sometimes true freedom is quieter. Sometimes it’s sitting in an AA meeting in Los Angeles with a bandage across your nose that says to the world, yes, I chose this life.

And I wouldn’t have it any other way.